On Noah Becker

Song of Myself:

Noah Becker’s Commedia dell’Arte

by Donald Kuspit

I have been a stranger in a strange land.

—Exodus 2:22

Noah Becker, Baby on a Rock, 2020.

Acrylic on canvas, 60 by 48 inches.

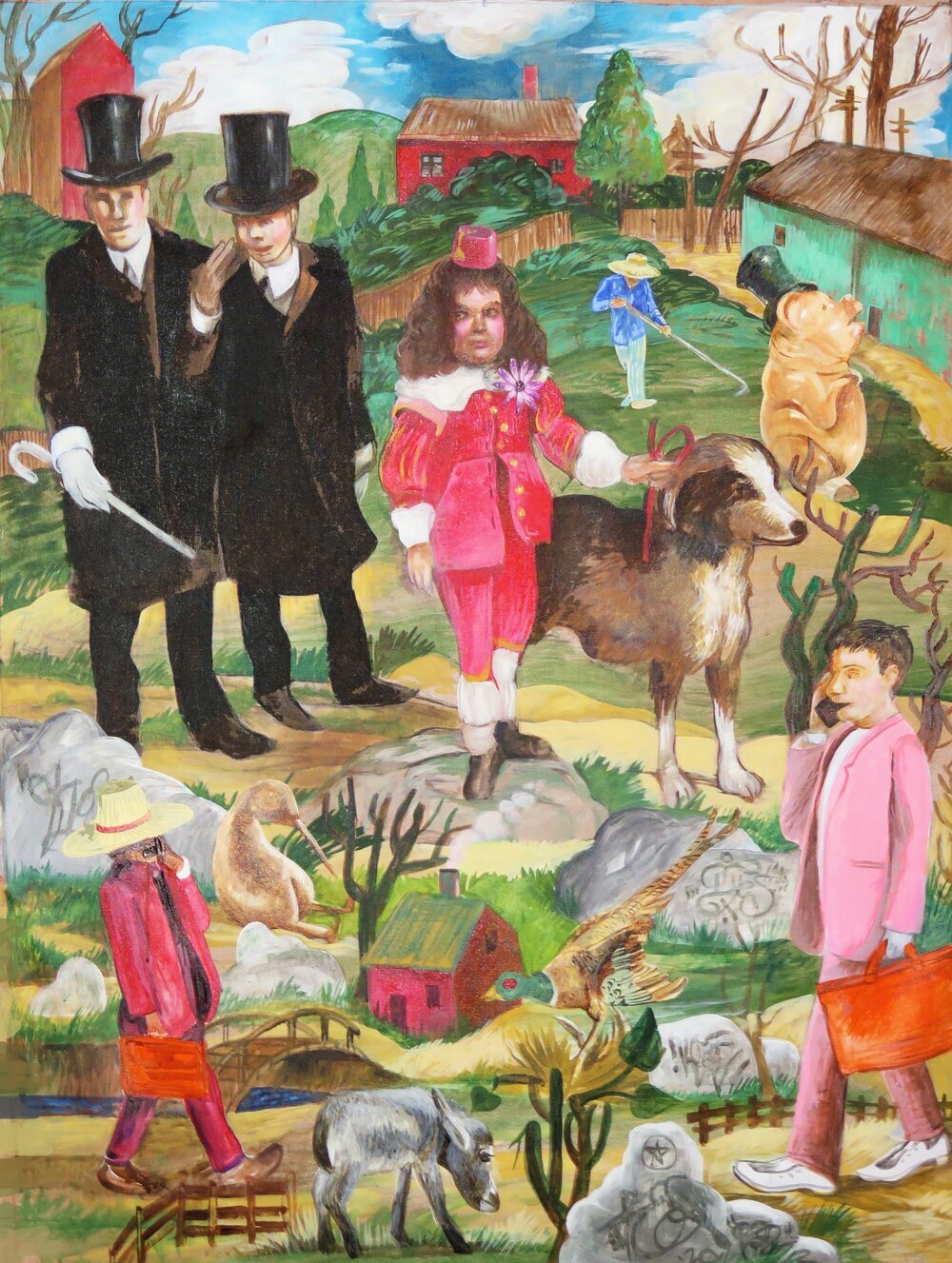

There’s Noah Becker, again and again, first as a Baby on a Rock, 2020—what Freud called an “imperial infant”—and then as Little Lord Flauntleroy—still imperial, but now an adolescent artist on The Collector’s Ranch, 2019, eager to have his art collected, eager to become an art aristocrat, eager to join the club of the rich and famous. The great dog accompanying him is a typical attribute of royalty; one only has to look at the reclining dog in Velazquez’s Las Meninas, 1656 to get the point. The spritely dog, eager to be petted by his owners, in Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait of the well-dressed, aristocratic Mr. and Mrs. Hallet, 1785, leisurely taking their morning walk, is even more to the point, because it makes clear, if without Becker’s ironic wit, that the artist is the collector’s pet. It’s the price one pays for leisure and fame, and the determined Little Lord, in his bright red suit, with a large flower in his lapel—it’s an outlandish Oscar Wildean kind of outfit, designed to bring attention to oneself, or to flaunt oneself, as the Little Lord’s name suggests—makes radiantly clear.

Then, finally grown up, and dressed in everyday clothes—a black jacket, blue jeans, and snappy hat—there’s the rather sober looking, straight faced, subdued Becker. He’s no longer the arrogant Little Lord Flauntleroy, flamboyantly exhibitionistic, self-congratulatory, and surrounded by artworld grandees and hustlers busily making deals on their cellphones, but an isolated Figure on a Chair, 2019. No longer in the Never Never fantasy art world of The Collector’s Ranch, he’s become a disillusioned realist, alone in the wilderness, surrounded by graffitied rocks—rounded like breasts rather than upright like the singular phallic rock in Baby on a Rock, more of a throne than the down-to-earth chair, and also graffitied, that is vandalized. Awakened from the adolescent dream of instant success, he’s become serious, mature, reflective—no longer the blatant extrovert of The Collector’s Ranch but a thoughtful introvert. Becker’s been humbled—shocked?—by the real world, and with that stripped of the delusion of grandeur that made him the smugly knowing—with just the right touch of cynicism, as his smirk suggests—adolescent on The Collector’s Ranch, another prematurely celebrated immature artist, pompous and pretentious, a glorified juvenile delinquent.

Noah Becker, The Collector’s Ranch, also titled The Valley, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

Graffiti is a populist art, an outlaw art, an anti-social art—and an age-old art, for it has existed since ancient times. It has been argued that cave paintings are a form of graffiti, but they seem to have been sponsored by the community, whereas graffiti are made by individuals in rebellion against the community, for whether writing or drawing graffiti is usually “made on a wall or other surface (a hard surface, like a rock) without permission, and within public view,” and as such a criminal—anti-social—activity, that is, vandalism. The graffiti artist is an outsider rather than insider artist, as the Noah on The Collector’s Ranch is, but the real Noah—the artist who is a spontaneous True Self rather than a conformist False Self, to use the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s famous distinction—is a graffiti artist. The grandly dressed Little Lord Flauntleroy Noah is a False Self—dare one say a fake artist, making art that betrays himself, but meets social approval, art that is bought by wealthy insiders, like the high-hatted lordly collectors in The Collector’s Ranch—whereas the casually dressed, self-contained, down to Mother Earth Noah is a True Self, spontaneously making graffiti, socially disapproved but self-expressive outsider art. Defacing public space, graffiti are peculiarly personal, however anonymous the graffiti “artist”—for he is also a mark maker, image maker, sign maker—and he wants his “art” to be seen, even if it is unrefined “low art” rather than fine “high art,” to use a familiar distinction.

But then low (street) art is seen more often than high (museum) art, and has a more instantaneous effect, all the more so because it is spontaneously made rather than belabored. It tends to be timely and topical—a response to current events—rather than timeless, however much it may last until it is erased by public authority, a disgrace to society. It is at once paradoxically anonymous and personal, often no more than a number of letters signifying the name of the artist—a sort of handwriting on the wall marking an anonymous existence. Thus “Joe”—black letters on a golden ground—in Figure on a Chair—and the pink “Bro,” with the number “7” inscribed in the “o”—in Baby on a Rock. Between a rock and a hard place there’s always the relief of self-assertion in whatever abbreviated form, and with it the hope of recognition and empathy, without which it is impossible to live and flourish, as the psychoanalysts tell us. More to the art historical point, graffiti is a form of “signature painting,” more incisively to the personal—and existential—point than abstract expressionist painting, for the critic Harold Rosenberg the ne plus ultra of signature painting. Graffiti signature painting is a more concentrated, focused—and more communicative—signature painting than abstract expressionistic signature painting, for graffiti is writing meant to be read as well as seen, and as such is realistic as well as abstract, comprehensible as well as felt, legible and coherent rather than illegible and incoherent gesture, intimate not just grandly in your face.

Noah Becker, Figure at the Outskirts of a City, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

The same solitary Becker, dressed in the same everyday clothes, now standing upright, appears in Figure in the Field, 2019, looking somewhat forlorn, and Figure at the Outskirts of a City, 2019—a shadowy, distant New York, as the skyscrapers imply—looking desperate and depressed, as his shadowy face and clothing suggest. Again, graffitied rocks abound, as they do in every painting. Landscape with Rocks, 2019 makes their autobiographical meaning clear: it is a sort of dream picture of the 40-acre farm on which he grew up. It was on Thetis Island, off the coast of British Columbia, as he says—"no man is an island unto himself,” as John Donne said, but Becker seems to be, as his self-portraits suggest, and the island was rather rocky and relatively barren, as his paintings of the land suggest, but nonetheless it was his home, and he was ready to happily return to it, The Prodigal Son, 2019 once again a sleeping boy peacefully at one with it, perhaps looking forward to a Family Vacation, 2019. The land was rocky but cozy, the trees perennially green, the grass flourishing—all was not barren, however many rocks there were, stones to trip over but also stepping stones to art, for they were his first canvases, as the graffiti—his graffiti—with which he signed them made clear.

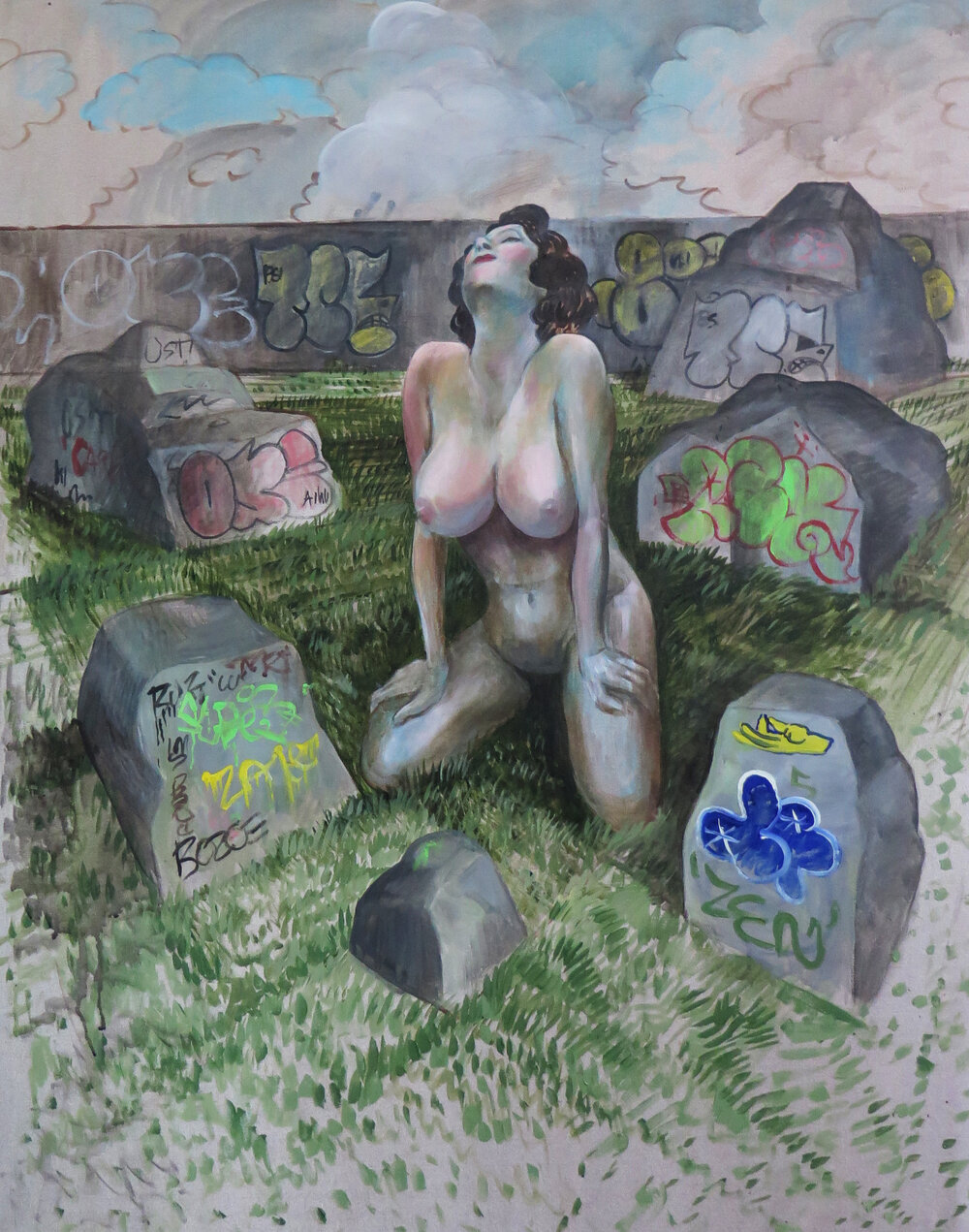

Noah Becker, Woman in a Landscape, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

Life on Thetis Island may have had its morbid moments, as Backyard at Night, 2019 suggests—the blackness of the grass suggests the depth of despair that could inform it—but it was also a place where one could have sexual fantasies to one’s heart’s delight, as Woman in a Landscape and Two Women Exercising, both 2019 suggest. Such naked women, with their perfect bodies and libertine air—especially the Woman in a Landscape, with her pornographically inflated breasts, unrealistic to the point of absurdity, making their promise of delirious pleasure all the greater (kneeling on the earth like a goddess, she worships the sun, and is worshipped by Becker, as her placement in the center of a shrine-like area set apart by four graffitied rocks, symbolizing his presence, indicates)—remind me of the Hollywood beauties that the director Billy Wilder famously said were mass-produced in Santa Monica. That is, however realistically rendered, they’re all stereotypes, and with that peculiarly unreal—make-believe, even mythical. I suggest, hopefully not to fancifully, that they are in unconscious fact symbols of Thetis, the small, sparsely populated Canadian island—2,560 acres and 389 people at last count—on which Becker was raised. The island was named in 1851 after HMS Thetis, a 36-gun Royal Navy frigate—an appropriate name, for an island is surrounded by water, and Thetis was a goddess of water. I suggest that the three beautiful nudes, with their divine bodies, in Becker’s paintings are symbols of the water goddess Thetis, and with it the island on which Becker grew up.

Noah Becker, Mini-Golf at Night, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

Now and then a real contemporary everyday woman in a dress would visit the island, as Woman with Cellphone and Woman with Cellphone in a Landscape, both 2019 suggest, but they’re not as alluring and available—at least in fantasy—as the two naked goddess-like women. They’re not busy on the cellphone, but shamelessly exposing their ideal bodies to Becker’s voyeuristic eyes, devouring them with desire. However sexually exciting, they’re indifferent to Becker, and not as ready for sexual intercourse as the kneeling woman in high black boots, long black gloves, wide black girdle, and panties, all tight-fitting sado-masochistic gear, in Mini-Golf at Night, 2019. She’s on a wooly white blanket on a golf-course green blanket on a graffitied rock. It looks like a sacrificial altar. She has a rectangular piece of transparent glass on her back, suggesting that she’s forbidden fruit, as it were—one has to lift the glass off her to penetrate her anally. Perverse aggressive sex—perversion, the erotic form of hatred, as the psychoanalyst Robert Stoller says, always has a ritualistic, formulaic rather than spontaneous, free-form character, especially when it is with anonymous, faceless, passive women. All the other women Becker depicts have faces, and are lively individuals rather than indifferent sex machines, passive instruments waiting to be penetrated by strong men. But it is all lurid fantasy, and the man seems castrated or inhibited—half a man, as the sculpture, mounted on a glass at its waist, suggests. The arm –or so it seems to be—on the grass next to the sculpture is particularly telling, for it is a phallic symbol, suggesting, if not castration, reluctance to hit the ball into the waiting hole. The painting is a brilliantly conceived nightmare—note the dazzling night sky—of a familiar male fantasy, straight out of the unconscious depths.

Dare one say that it is an ingenious updated rendering—surrealizing re-conceptualization—of the temptation of St. Anthony theme, just as Becker’s Supper, 2013 is an ingenious updated rendering of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, 1601, and with that a re-realization of its realism? Like Becker’s revisited Old Master paintings—noteworthily, his ironic “re-doing” or “re-thinking” of traditional portraits of great men, such as Velazquez’s Portrait of Philip IV, 1623-24 (distortion typically serves the purpose of irony for Becker)—they are certainly what in the Renaissance would be called brilliant invenzione.

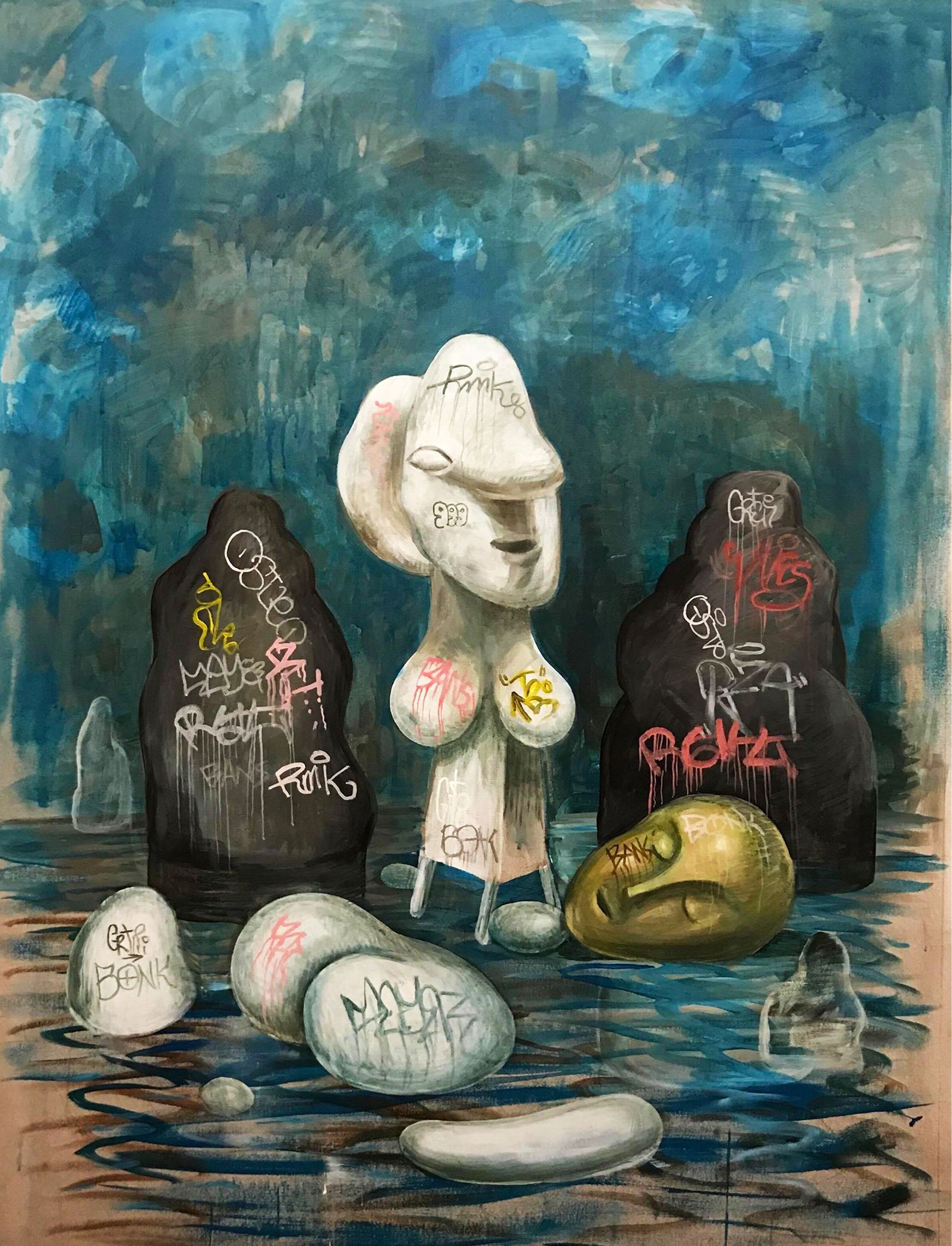

Noah Becker, Still Life, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

As Repository of Cultural Objects at Sunset and Still Life, both 2019 strongly suggest, modern art is passé, not to say a dead letter for Becker. Littering a wasteland, we see Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse, 1910 and one of Picasso’s surrealized female figures, nose and breasts grotesquely enlarged, the latter graffitied, as though touched with ironic desire, not to say manhandled. It’s woman as muse, a sleeping beauty, mind in no need of matter, that is, a head without a body, and woman as ugly monster—what the psychoanalysts call a phallic woman, as her prominent, bloated nose suggests. They’re both still lifes—dead art—but the two black rocks that flank them are alive with explosive graffiti, some of it luridly red, all of it restlessly intense, certainly compared to the sculptures, solemnly self-contained, certainly inexpressive and dispassionate in comparison, however monstrous and intimidating the Picasso and sublime and seductive the Brancusi. Becker has staged what in the Italian Renaissance was called a paragone, a debate between painting and sculpture, in his painting between sprawling gestural graffiti—raw art—and insular sculpture—refined art. More pointedly, between manically vital self-expression and depressing impersonal semi-abstract art.

Noah Becker, Repository of Cultural Objects at Sunset, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

The Picasso head appears again in the Repository of Cultural Objects at Sunset, now alongside a Henry Moore sculpture of a reclining woman—a hollowed out odalisque, as the hole in her body suggests, and a faceless one, for she has no features. She’s the shell of a woman, as anonymous and dehumanized as the distorted Picasso head. Other dead “cultural objects” litter the landscape, alive with green grass, among them what seems to be an Easter Island head and a Neolithic temple—primitive sculpture and primitive architecture, both influential on modern art. And again they are adorned with graffiti, their stone appropriated in the act of being vandalized, their hardness softened by being humanized with writing, more mysterious than they are because more anonymous—initials of nameless individuals, all but meaningless and unimportant compared to the cultural objects, art historically significant, certainly compared to the “artless” letters that mock them. It’s sunset for the cultural objects, but sunrise for graffiti, as the blazing red letters over the entry to the prehistoric structure—a tomb? The point is driven home by Sunset, 2019: the gray stone of the primitive figures and abstract configurations is marked with colorful graffiti, bringing them to aesthetic life.

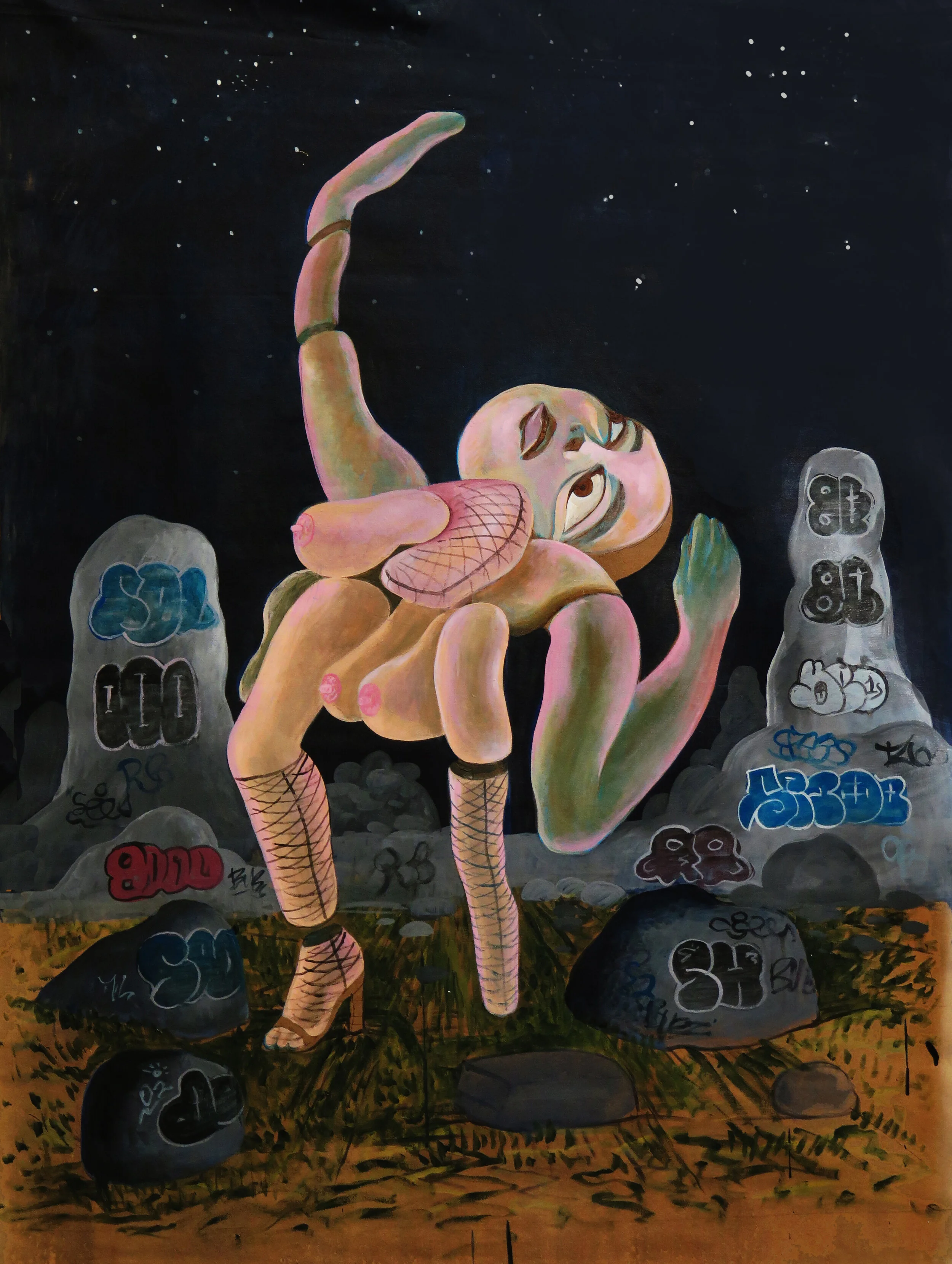

Noah Becker, Night Ritual (For Hannah Höch), 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.

However much Becker takes down—desecrates—famous works of modernism, more broadly, world-famous cultural monuments, in the name of the anonymous artists of the present—the graffiti artists, who breath fresh new life into tired old art, and into indifferent society at large—Becker is a modernist despite himself, as Night Ritual (For Hannah Höch), 2019 suggests. Hannah Höch was a leading Dadaist, and her sardonic Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany, 1919-1920 is the quintessential Dadaist work. Dadaism declared that “art is dead”—traditional art, high art, fine art—and so does graffiti art. One might say it is a more condensed, insidious Dada art, using writing rather than images to make its ironical, critical point, rather than the social imagery that Höch uses. She also uses text, but it is from newspaper clippings and posters, and as such public, rather than peculiarly private, as graffiti signatures are. Indeed, graffiti is a private invasion of public space—an “identity politics” carried to an almost nihilistic extreme, that is, an assertion of individuality in defiance of society. Höch’s work is famously democratic and realistic, as its use of graphic photographic imagery shows—rather than aristocratically abstract, as Picasso’s, Brancusi’s, and Moore’s art is—picking and choosing, seemingly randomly, images from the common culture. One might say her work is not pretentiously original, but makes original use of mass cultural reproduction.

Is Becker’s perversely distorted female figure—with one crippled leg and three breasts, two between her legs and serving as a torso, the third projecting from her right armpit—a sardonic Dadaist portrait of Höch? She seems to be a mannequin—a dummy—that has had a bad fall and can’t exactly be put together. She clearly conveys Becker’s ambivalence about women—about their bodies. To my art historical eye, Becker’s grotesquely distorted female doll has more to do with Hans Bellmer’s broken female dolls, their body parts more or less randomly strewn, some lost and never to be found—they’ve had a bad fall from which they can never recover. Becker puts the body parts of his bizarre doll together, doing as best he can, but his female Humpty Dumpty has had a bad fall and can never again be put together correctly, not only because some of her parts are missing but because she was surreally absurd to begin with. One might say it’s an infantile view of the female body, considering the psychobiological fact that in the first year of life the infant sees the mother’s body as a sum of body parts—what psychoanalysts call part objects—that do not add up to an integrated whole. It is highly probable that surreal figures—conspicuously Picasso’s—are informed by a similar infantile—emotionally primitive—and characteristically adolescent male—outlook. One wonders if they are not informed by what the psychoanalyst Wolfgang Lederer calls unconscious male hatred of woman, informed by the fantasy that, however beautiful, she’s a castrator—a femme fatale. So why not destroy her before she destroys you? But Becker remains phallically intact—and detached—as the totemic rock, signed by his graffiti, between which the female doll in Night Ritual (For Hannah Höch) is crucified, makes clear. All the rocks in his field of dreams symbolize his ego strength. Rock solid, he holds his own against any threat to his integrity, whether from bosomy women or museum art, his graffiti art subverting and castrating it.

Becker’s style is what I would call a people’s style, that is, a style of the common culture, rather than an elite style, a style for the socially privileged. More particularly, it is a comic style, for it mocks whatever it touches, as graffiti does. He offers us cartoon versions of modern works of art, trivializing their supposed originality, cutting them down to everyday size: the idols of modern art become corny shadows of themselves, making them banally familiar rather than abstractly unfamiliar. All of his figures—works of art and human beings and rocks, figures in their own ironic right for they have been humanized by being labelled with graffiti signatures—are actors in a commedia dell’arte. There is a perverse canniness in Becker’s pictures, a critical edge to his graffiti, a cunning irony in their staging, as there is in commedia dell’arte, sometimes called commedia dell’arte all’improviso, that is, improvised comic theater. All of the actors in such an improvised theater are caricatures of human beings—human stereotypes given an ironical edge. Graffiti art is improvised art, and a caricature of art, and as such the perfect “sign language” for Becker’s comic performances. The farmland of his Canadian island is a theater on which his actors and actresses perform. As in traditional commedia dell’arte, they are all stock characters—stereotypical females, stereotyped works of art, and Becker, a sort of mute Harlequin, as he is in the traditional commedia dell’arte. Sometimes he is on stage, sometimes he is symbolically present in the form of the rocks, as his signature graffiti suggests, orchestrating the scene if sometimes from the wings. Carrying his baton or slapstick (paintbrush), the Harlequin can change the scene at will, participating in it or not but controlling it—stage-managing it.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, an American city, and raised on Thetis Island, a Canadian island off the coast of British Columbia, and traveling between there and New York City, where he has a studio in Brooklyn, Becker is a kind of displaced person with multiple personalities, for he is an accomplished jazz musician, founder and editor of an online art magazine, an art writer and critic as well as a painter. He is a man-about-art-town, a citizen of two very different countries and similarly divided countries, and remarkably and relentlessly creative, with a wide-ranging knowledge of the history of art. He is a citizen of the artworld, restlessly everywhere but at home nowhere, not even on the farm on which he was raised, for it is haunted by the ghosts of unrequited love, symbolized by the various females that appear in his pictures, their anatomies distorted by his ambivalent desire. New York is the dream city in the background of Figure at the Outskirts of a City, but like the magical kingdom of Oz it is a mirage—certainly not as solid as the ground of his Canadian farm, not as real as the houses on it. In all his self-portraits Becker is a stranger in a strange land—at home nowhere, and so in peculiar exile everywhere—and as such suffers from what the existentialists call “dreadful freedom.” He has made the creative best of it, that is, achieved authenticity and autonomy, the self-containment of a person who knows himself, who has become a true self. If a self-portrait is a mode of self-discovery, then Becker’s self-portraits are self-critical self-explorations, a means of taking stock of oneself. Finding and mirroring oneself in a self-portrait confirms that one exists, however much one feels like an illusion.

Noah Becker, Figure on a Chair, 2019.

Acrylic on canvas, 48 by 36 inches.